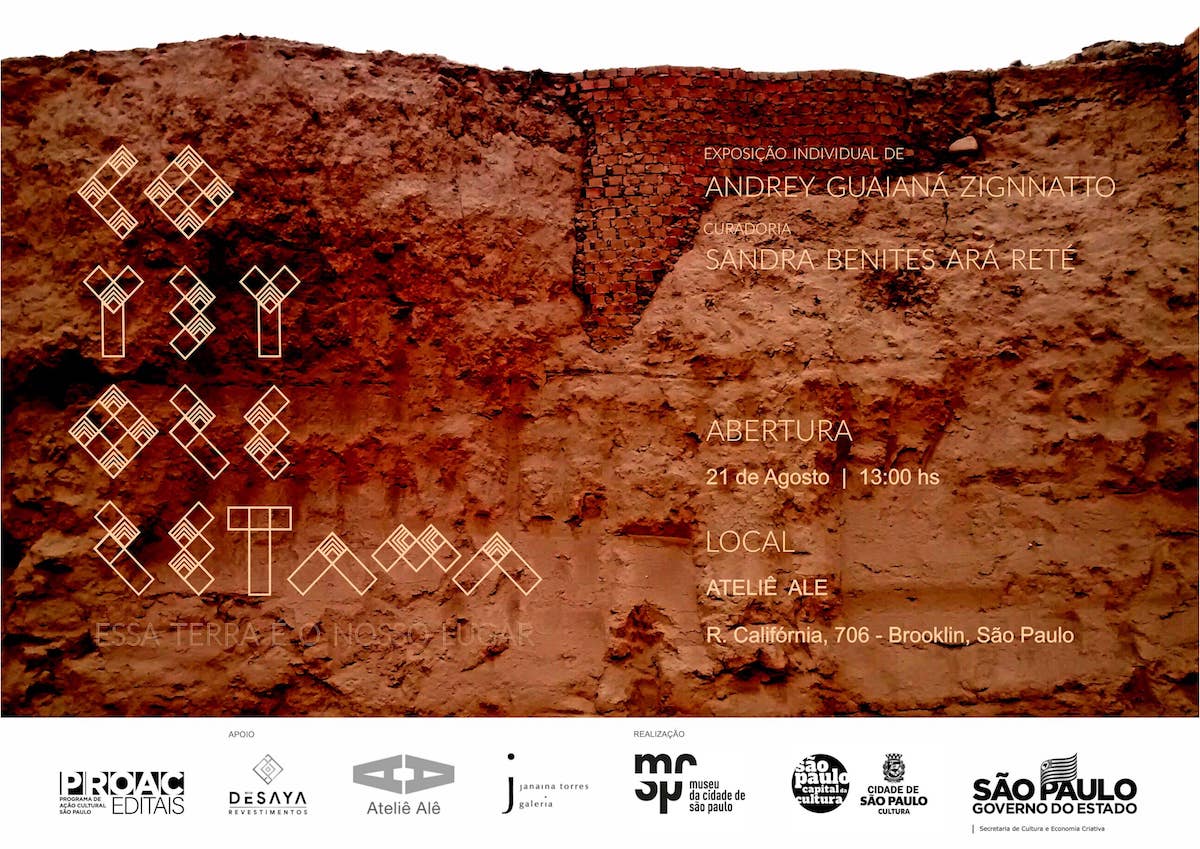

CO YBY ORÉ RETAMA – Essa Terra é o Nosso Lugar

[CO YBY ORÉ RETAMA – This Land is Our Place]

Andrey Guaianá Zignnatto

Curatorship

Sandra Ará Reté Benites

Opening: 08/21

Exhibition period: from 08/21 to 09/17/2021

Andrey Guaianá Zignnatto is the heir of indigenous grandparents from the villages of Inhampuambaçu who were silenced by the colonial city of São Paulo de Piratininga, a place later dominated by bricks and concrete of houses and buildings that today occupy almost all the land of this megalopolis. A self-taught artist, visual arts teacher and social project activist, the artist worked as a mason’s helper from the age of 10 to 14, a descendant of the Tupinaky’ia and Gûarini peoples. These ancestral affective memories are the basis for the conceptual development and methods used in his artistic production.

In the current condition where many originally indigenous territories are covered by concrete, it is difficult to think of the idea of a place to make a fire in the urban context, a traditional custom of the original peoples to form the educational space and transmit ancestral knowledge through orality, among many others of their values violated and buried in these territories. For this reason, when indigenous peoples who had their cultural universes erased decide for the process of resuming their ancestry, despite this process starting from symbolism, it transcends mere symbolic questions. The expression of a sense of belonging is built in the field of images, narratives, memories for a place of life and spirituality.

Andrey Guaianá Zignnatto begins his career as an artist based on his memories of the time he worked as a mason and on the knowledge acquired by this profession. In his most recent works, the artist’s shift from questions about civil construction to questions about his indigenous ancestry is evident. It is possible to observe in the works presented in the exhibition elements that demonstrate the artist’s effort to reorder his thoughts in this trajectory, from the urban context to the indigenous context, an effort to equalize the forces of these very different universes. In this sense, it is possible to state that the artist; like so many other contemporary indigenous artists; found in art and its poetic potential instruments that have collaborated to imagine and carry out this possible resumption, and to reinhabit the Tekoha (where

produce a collective way of being), the place originally organized and inhabited by indigenous peoples, a space for the production of knowledge to safeguard ancestral rights.

Here, it is also important to draw attention to the risks and necessary precautions regarding the still constant approaches to indigenous peoples’ issues from colonizing perspectives. Care not to romanticize ancestry too much, as if Brazil were “discovered”, as if indigenous populations of different ethnicities were passively “civilized”, and above all what and who defines someone as an indigenous person. Hence the importance of the indigenous people who were silenced putting themselves in evidence, as well as a reaction of the original peoples who always struggled to resist the invasions, and, in the case of those who choose the paths of the arts, to demonstrate how fiction is also an important device in these political-identity retakes, similar to what, as Oswald de Andrade denounced, was/is for coloniality. It is not, therefore, a question of thinking of the prefix re necessarily as a rescue or a return to a point supposedly prior to the colonial invasion. For this reason, it is relevant to think that the exhibition space and the production of indigenous artwork are not just any place and work.

The work of an indigenous artist is a work that comes from the attempt to translate the indigenous struggle in favor of the physical territory and also the subjective space of thought. This work is very special because of that, because it translates this movement of resistance, survival and expansion in these spaces. She is not just a simple object, but the result of ancestral and transcendental knowledge. This work is an attempt to translate the thoughts and creativity of collectives, which should not be seen as just one individual, the artist. The importance of the collective for the individual and of the individual for the collective is essential in indigenous art. We are never represented in art by just one individual. And this work created by indigenous artists appears in a way that replaces this thought about the individual within a whole, and the relationship of this individual with this whole. There is no indigenous work without this encounter and this knowledge that is produced by the collective. The work is materialized by the individual, but thinking is a process that occurs in the collective. Although Andrey’s work speaks of his family’s historical process, it also speaks for all the other indigenous people who were buried in cities by tons of concrete indifference.

It is difficult to find in words a way to explain everything that is unique and special, what is transcendental, what is directly associated with the beings of the earth. The body, social relationships, well-being, good living is in intimately related to the surrounding elements, society itself, the elements of the earth, forests and animals, the spirits. It is not possible in indigenous thought to disassociate these relationships. And it is in art that the indigenous find a way to translate the complexities of these relationships.

It is important and necessary for the (non-indigenous) Juruá to understand these other ways of thinking, such as these different indigenous perspectives. Indigenous art is yet another alert in an attempt at dialogue between indigenous peoples and these Juruá, which offers them other ways of seeing beyond the huge concrete walls and asphalt floors, and seeing what unites us in a relationship of respect as humans. , and together what unites us with the non-human in a respectful relationship also with the Ijá do Rio, Ijá da Mata, the guardians, the spirit of the land, the spirit of the forest, the spirit of the trees. These are some reflections that can be found in the works of Andrey Guaianá Zignnatto, which are part of the exhibition CO YBY ORE RETAMA [This Land is Our Place].

July 06, 2021

Sandra Ara Rete Benites

JAIKO JEVY, JAJAPO JEVY HÁ’E KUEPY

Andrey Guaiana Zignnatto má nhande kuery ramyminõ yma ramo ikuai va’ekuery Inhapuambaçu tekoa oin raka’e São Paulo já’eambyte re ayn ramo ita gui meme má opamba’e oin, ha’e má kyrin vy oiko axy raka’e va’eri ayn há’e nhombo’e va’e oiko, Guarani regua’i havi oiko tupinaky’i re oje’a i va’ekue. Va’eri há’e arandua oguereko va’e rupi meme Ju tembiapó oexauka

Ayn gui ita pa oiny yma ramo nhandeva’e Kuery ikuai raka’eague rupi ramo tetã re jaiko vy mamo rantu nhamoendy tataypy jaguapy aguã nhamombe’u aguã nhamdereko há’e opamba’ereko regua re, há’e va’e aepy nhende Kuery reko, ka’aru maramo jogueroguapy ayvu Porã omombe’u. Oiko pete’in Mby’a heta omomba rai’i va’ekue rembyre’i má ayn gui ojevy jogueravy ha’e yvy re joguero’a avi aguã.

Andrey Guaiana Zignnatto má nhande kuery ramyminõ yma ramo ikuai va’ekuery omboypy tembiapó Oiko pete’in Mby’a heta omomba rai’i va’ekue rembyre’i má ayn gui ojevy jogueravy ha’e yvy re joguero’a avi aguã Ayn gui ita pa oiny yma ramo nhandeva’e Kuery ikuai raka’eague rupi ramo tetã re jaiko vy mamo rantu nhamoendy tataypy jaguapy aguã nhamombe’u aguã nhamdereko há’e opamba’ereko regua re, há’e va’e aepy nhende Kuery reko, ka’aru maramo jogueroguapy ayvu Porã omombe’u. Oiko pete’in Mby’a heta omomba rai’i va’ekue rembyre’i má ayn gui ojevy jogueravy ha’e yvy re joguero’a avi aguã.

Nhande Iporã vaipa ramo katu há’evete tove katu anhete toimba Porã i katu opamba’eramo jepe koo yvy re nhandekuai porã, aguã rupi katu nhande kuery ramyminõ yma ramo ikuai va’ekuery regua há’e katu imbaraete aguã já’eambyte re ayn ramo ita gui meme má opamba’e oin, ha’e má kyrin vy oiko axy raka’e va’eri ayn há’e nhombo’e va’e oiko, Guarani regua’i havi oiko tupinaky’i re oje’a i va’ekue. Va’eri há’e arandua oguereko va’e rupi meme Ju tembiapó oexauka jaguapy aguã nhamombe’u aguã nhamdereko há’e opamba’ereko regua re, há’e va’e aepy nhende Kuery reko, ka’aru maramo jogueroguapy ayvu Porã omombe’u. Oiko pete’in Mby’a heta omomba rai’i va’ekue rembyre’i má ayn gui ojevy jogueravy ha’e yvy re joguero’a avi aguã.

Apy ma ore rojapo ojejoko aguã orea katy. Apy guima nda`eve vei ma amboekue oaxa aguã ore yvy ma Há`e rami ma, oiko ay gui, orevy o Kaninde pe iporãvea rami merami rojapo há`e va`e Indigena kuery ay gui ikuai va`ema, yma pyguare rami he`y… Yvy ojeporua voi amboae rami, yvy rupa omba`e rami ae oiporu oikoa`i rupi oi aguã yvy ranhe rã oipe`a oipe`e eravy nhandegui, ha`eguima oiporuxea rami rive tema ojapo ha`epy ikuai va`ere. Ijayua jave Brasil, vyma oexaã ramo yvy rive rami, nação rami he`y nhande rexa, vyma Brasil ma yvy oi rivea rami jaikuaa? Vy há`ema jajogueroa yvy re.

Yvyty manje ojoua rami omombe`u vyma oo Paraty peve ogueraa aguã há`egui navio pyju, há`erami onhemombe`u oiny. Tape puku ojeporu va`ekue apy ikuai aema va`e kuery, ojuka há`egui o escraviza pa mavy rive. Jaexa porã ramo há`e rami voi: yvy oi porãve aguã ambikuai hague rupi rive oi ovy. Apy ma nda`ikuai yvyre hekoa`i va`ekue anho`i he`y, ikuai avi jurua kuery oejaa rive tape rupi va`e kue voi, há`e rami ojejapo ovy já`e aguã rami rivema aema oi. Nhandero aguã yvy nda`eve vei ma, nhande jopy parei ma,

ambo`ekue reve nhande kuai aguã joupive`i pave voi. Yvy`ã, ka`aguy, yakã, ija va`e meme ikuai vy jepe ma, ay gui oiporua mba`emo ojou aguã rive etema. Andrey Guaianá Zignnatto ayvu rupi rive há’eva’e CO YBY ORE RETAMA [Esta Terra é Nosso Lugar] He’i va’e regua

Tradução para Guarani M’bya: Anthony Karaí Poty